The

big news after President Obama’s State of the Union address in January

was that he didn’t really talk about the issues of inequality that

everyone expected him to talk about. Instead, he shifted the

“conversation,” as we call it, toward the subject of opportunity. He

shied away from the extremely disturbing fact that when you work these

days only your boss prospers, and brought us back to the infinitely less

disturbing fact that sometimes poor people do get ahead despite it all.

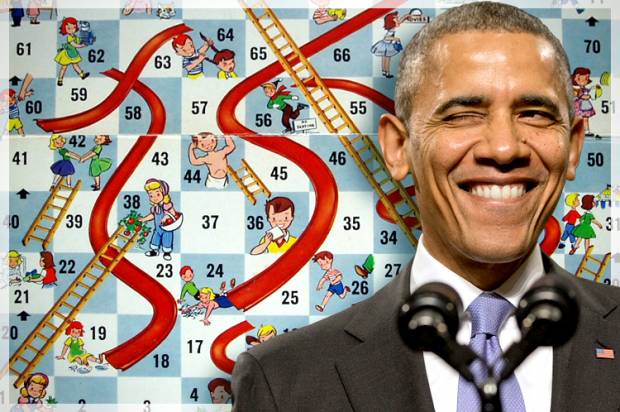

In a clever oratorical maneuver, Obama illustrated this comforting idea

by referencing the success stories of both himself—“the son of a single

mom”—and his arch-foe, Republican House Speaker John Boehner—“the son

of a barkeep.” He spoke of building “new ladders of opportunity into the

middle class,” a phrase that has become

The

problem, as Obama summed it up, is that Americans have ceased to

believe they can rise from the ranks. “Opportunity is who we are,” he

said. “And the defining project of our generation must be to restore

that promise.”

The switcheroo was subtle, but if you’ve been

paying attention you couldn’t miss it: These were almost precisely the

words Obama had used the month before (“The defining challenge of our

time”) to describe inequality itself.

Well, the Democratic apparat

heard it, and as one body did they sway and swoon. This was a move of

statesmanlike genius, they said. “Opportunity” and social mobility are

what Americans have always liked to hear about, they declared;

“inequality” sounds like a demand for entitlements—or something much

worse. “What you want to do is focus on the aspirational side of this,”

said Paul Begala in a typical remark, “lifting people up, not on just

complaining about a lack of fairness or inequality.”

If you’re in

the right mood, you might well agree with him. In the distant past,

“opportunity” used to be something of a liberal buzzword, a way of

selling welfare-state inventions of every description. The reason was

simple: true equality of opportunity is not possible without achieving,

well, greater equality, period. If we’re really serious about

opportunity—if we’re going to ensure that every poor kid has a chance in

life that is the equal of every rich kid—it’s going to require a

gigantic investment in public schools, in housing, in food stamps, in

infrastructure, in public projects of every description. It will

necessarily mean taking on the broader problem of the One Percent along

the way.

But

that was what the word meant long ago. It’s different today. When

people talk about opportunity nowadays, they’re often not trying to

refine the debate over inequality, they’re trying to negate it. The

social function of mobility-talk is usually to

excuse

inequality, not to change it; to persuade us that the system we have

now is fair and even natural—or that it can be made so with a few more

charter schools or student loans or something. Because everyone has a

chance at making it into the One Percent, this version of “opportunity”

tells us, there’s nothing wrong with letting the One Percent hog every

dish at the banquet.

The well-known libertarian economist Tyler Cowen, for example, writes in his new book “Average is Over”

that we increasingly inhabit a “hyper-meritocracy” in which “top

earners” take home more than ever before because, duh, they’ve got the

right skills and hence they deserve

to take home more than top earners ever have before. The future might

look bleak for less-than-top people like you, but if you fall off the

ladder of opportunity there’s only one answer: Get used to it.

2. But

let’s put all that aside for now. Let’s assume, for a moment, that a

real meritocracy would be an awesome thing to have; that giving every

person a chance to run the Race to the Top is a worthy goal of

government policy.

Even with those assumptions it’s not so simple.

Why should Americans work to ensure that everyone has a fair chance to

join the ruling class, if the great principle of that ruling class is

unfairness? Why should Americans compete on the level if what we’re trying to win is admission to a fraternity of thieves?

Let

me explain. A meritocracy requires more than simply making it possible

for people at the bottom to climb the ladder of opportunity. It also

involves chutes of accountability for those at the top. These are two

sides of the same coin: the skilled must be able to rise, but grandees

caught with their snouts in the trough must also come tumbling down. “We

cannot have a just society that applies the principle of accountability

to the powerless and the principle of the forgiveness to the powerful,”

writes

Chris Hayes in his sweeping meditation on meritocracy, “Twilight of the Elites.” And yet: “This is the America in which we currently reside.”

Is

it ever. Recall for a moment the situation in which Barack Obama was

inaugurated in 2009. During the preceding decade, we had endured a tech

bubble and a housing bubble; our accounting industry had been suborned

in all sorts of ways; our prize stock analysts had been suborned in all

sorts of different ways; our leaders and foreign-policy pundits had sold

us a war in Iraq using completely bogus reasoning; our investment

houses specialized in cooking up poisoned investments; our ratings

agencies specialized in hanging blue ribbons on them; and the executives

of our financial industry specialized in helping themselves to

stupendous bonuses even as they lost billions—even as they blasted holes

in the economy of the world.

What Americans understood when we

looked over this panorama of fraud and incompetence and self-dealing was

that expert authority had been corrupted at every point where it was

exposed to organized money. The meritocracy was obviously broken.

Public

revulsion against this incredible state of affairs is what delivered

Barack Obama to the presidency, and we rightfully expected him to

address the problem. His resounding failure to do so outweighs all his

noble statements about studying hard and climbing ladders of

opportunity.

The distressing fact is that Obama had perhaps the

greatest chance of any president in recent years to smash the barriers

that keep the talented from climbing the ladder, and he chose to do

nothing. The sledgehammer was in the president’s hands, the nation was

cheering for him to start pounding—and he walked away from the job.

Oh,

he is ready to hold kids and teachers accountable, all right—to make

sure they all take some Big Test and are sorted accordingly. There have

been a few other bright spots as well. The people he has put in charge

of the EPA and the Labor Department no longer try to subvert their own

agencies, as they did in the Bush years. He appointed the capable Janet

Yellen to run the Fed. And: He meted out a satisfying ass-kicking to

upper-class twit Mitt Romney.

The other side of the ledger? Well.

Obama continued virtually unchanged the Bush Administration’s bailout of

the banks that were—let us never forget—the

culprits

in running up the housing bubble and vectoring its toxins into the

economic flesh of the world. He declined to put obviously failed banks

into receivership, as the standard practice has always been, and he

didn’t remove incompetent bank management in any numbers, as was common

with bank bailouts during the Roosevelt Administration. On the contrary,

his officials seemed to forget how to negotiate when negotiating might turn out to be costly to bankers. They twisted themselves into pretzels

to avoid wielding their ownership stakes in the various financial

companies they rescued. In one infamous instance Obama’s team did the

exact opposite of accountability, making sure that bonuses went out as

scheduled to the AIG division responsible for the instruments that

wrecked the company, thus rewarding the fuckups. After that they fanned

out to the talk shows to insist on the sanctity of contract—a

inviolability they find it easy to violate when it is autoworkers or

homeowners on the other side of the table.

There was a mysterious inability to get “excessive pay”

under control at bailed-out banks, and so few prosecutions of the

banksters who did all this to us that Obama’s Justice Department made

George W. Bush’s Justice Department look like an Everest of moral virtue. In a 2012 speech, the head of Obama’s Criminal Division even announced in a public speech that

he was sometimes persuaded when banks and corporations asked him not to

prosecute because that might cause the company in question to fail and

thus hurt the economy—a courtesy that American prosecutors extend to no

other group of professionals and that, by its nature, makes a joke of

the idea of equality before the law. Obama can hand out full college

scholarships to every single toddler deemed worthy, and he will never

recover the faith in fair play that one speech destroyed.

It goes on to this day, even as the Wall Street bonuses mount to ever more dizzying heights. In a report issued last month

, a Senate subcommittee tried to persuade the Justice Department to get off its ass and take action against American clients of certain Swiss banks, nearly six years after newspapers first reported

that those banks had helped those ultra-wealthy clients to evade taxes.

But it seems the Justice Department is just not that into the idea of

getting tough with banks. Here is the first sentence of a story in Friday’s New York Times:

Four

years after President Obama promised to crack down on mortgage fraud,

his administration has quietly made the crime its lowest priority and

has closed hundreds of cases after little or no investigation, the

Justice Department’s internal watchdog said on Thursday.

And

that’s the age of Obama: The standardized tests are for real, but the

stress tests are often for show. Accountability for thee, but not for

me.

3.

In a 1984 book

on the problem of inequality, the journalist Thomas Edsall wrote that

one of the Democratic Party’s historical contributions to equality was

its practice of promoting members of outsider groups to positions of

political authority. He meant this as a description of the distant past

and, indeed, I don’t know of any other commentator on the subject who

mentions the practice at all. It is completely forgotten.

Well,

it is worth thinking about again. Not because Democrats should revive

the politicized hiring practices of one hundred years ago, but as a way

of assessing Barack Obama’s record as a champion of opportunity. If the

president truly believes that careers should be open to talent—the

central idea of meritocracy—then surely he has always taken pains to

apply that philosophy when choosing his own team. Surely he sought out

the very best people for the momentous job at hand.

I confess here

that believing Obama would act in this way was one of my reasons for

supporting him back in 2008—the hope that this thoughtful and talented

man would bring a completely new crowd to D.C. and break the grip of the

Clinton-era centrists on the Democratic Party. After all, they were the

ones who deregulated the banks in the first place—who did everything

they could to get NAFTA passed, to cheer for the New Economy, to

“reinvent government,”

and so many other noxious things. Surely, with the world prostrate and

gasping after a dose of their medicine, they would not simply be invited

back to write another prescription.

I will also confess

that Obama’s subsequent failure to follow these meritocratic rules

astonished me in a way that we cynical types don’t like to be

astonished. When Obama won, I figured it was opportunity time—let’s see

who climbs the ladder. Instead, he brought Clinton Administration

Treasury Secretary Larry Summers back as his chief economic adviser.

Clinton enforcer Rahm Emanuel became Obama’s Chief of Staff. Timothy

Geithner, architect of the disastrous AIG bailout, became the new

Treasury Secretary. Clinton veteran Jack Lew eventually succeeded him.

Gene Sperling came back too, to run the National Economic Council.

Five

years later, I am now quite convinced that it doesn’t matter what the

needs of the moment are; the personnel in this town will

always

be the same. Change the subject to inequality, or to poverty, even, and

still—thanks to the magic of D.C.—the same crowd of former bankers and

arch deregulators will emerge as the go-to guys. You’ll get Larry

Summers, again! Robert Rubin—one more time!

Hell, you could even announce an initiative on getting new people and

new ideas into the federal government and when the music stopped it

would turn out to be their protégés sitting in the distinguished chairs.

Another

thing about this cozy crew: Many of them have worked in the banking

sector for long enough to make them intimate members of the nation’s

topmost class. Chris Hayes mentions this charming aspect of the Obama

bunch in a memorable passage of “

“Consider the routine staffing

changes in the Obama administration as it reached the midway point of

its first term. Chief of Staff Rahm Emanuel left his position to run for

mayor of Chicago. Emanuel got his start as a fund-raiser for Mayor

Daley, moved to the Clinton White House, where he lasted nearly the

entire eight years, eventually becoming a senior adviser to the

President. After serving in the Clinton administration, at the age of

thirty-nine he left to become an investment banker, spending two and a

half years at Wasserstein Perella, where he amassed a fortune of more

than $18 million. He then ran for Congress, became White House Chief of

Staff, and left to run successfully for mayor of Chicago.

“To

replace the multimillionaire Rahm Emanuel, the multimillionaire

president Barack Obama . . . named multimillionaire William Daley, the

brother of the mayor that Emanuel was hoping to replace. Daley’s resume

included stints as commerce secretary in the Clinton administration and

as campaign manager for Al Gore’s 2000 campaign, but at the time he was

named chief of staff, he was Midwest chairman at JPMorgan Chase, making

$8.7 million a year. . . . When Bill Daley later left his post as chief

of staff in January 2012, he was replaced by Jack Lew, who spent four

years at Citigroup and received a bonus of $950,000 in 2009, even after

it was disclosed that his division made high-stakes bets on the housing

market.”

What

makes this infuriating is that Barack Obama seemed to have different

ideas once. He was going to “Close the Revolving Door on Former and

Future Employers,” declared his 2008 campaign website, Change-dot-gov. (It also promised—be still, my grinding teeth—to “Protect Whistleblowers.”)

It

is even more infuriating to realize that the correct answers to the

test have been available to Professor Obama all along. Back in September

of 2008, when the financial crisis was gathering speed, I was writing a

column for the

; in my efforts to

comprehend the disaster, I learned that the nation’s foremost authority

on the type of fraud that had wrecked the economy was a former S&L

regulator named Bill Black. I went on to ask Bill Black’s opinion

probably dozens of times; as the years passed and the crisis deepened,

Bill Black went on to be quoted by just about everyone and to become

probably the most famous former S&L regulator in the world. His

doctrine of “control fraud” is today familiar to anyone trying to

understand what went wrong in 2008.

Another group that

sought out my friend Bill Black during the crisis year was the Obama

campaign. For them he narrated a twelve-minute campaign video,

describing at length the involvement of Republican candidate John McCain

in the Keating Five scandal, and faulting McCain for choosing a zealous

deregulator as his chief economic adviser—“he’s picked the worst

possible source of advice.”

(

You can watch the video here.)

When

Obama won the presidency, I assumed that Bill Black would soon be

moving to Washington to usher prominent bankers through their perp

walks. That’s what opportunity and meritocracy meant, after all. You

bring in the guy who understands the problem.

Of course it never

happened. His phone never rang. There was no ladder of opportunity for

him or anyone like him, precisely because they represented

accountability. And Barack Obama, champion of meritocracy, went on

instead to pick the second-worst-possible source of advice.

When I

ask Bill Black now what these last few years tell us about fairness and

meritocracy, he refers me to Gresham’s law. “If you gain a competitive

advantage by cheating,” he says, “then you won’t get a meritocracy,

you’ll get a system where cheaters prosper and bad ethics drive good

ethics out of the market.” Is that what kept him out of Washington, I

ask? Yes, in part. It’s “the international race to the bottom, which the

administration has largely adopted. ‘We can’t crack down [on the banks,

the administration thinks,] they’ll all move to the City of London. We

need to have the JOBS bill,’ a godsend to fraudsters, ‘because too many

IPOs are being done in China instead of the United States.’ ”

“People

like me were moved out long ago,” Black concludes. To a government

“trying to signal continuity and friendliness to the banks,” his

presence would have been, he supposes, more than a little discordant.

So

our generation gets to rediscover that “the race is not to the swift,

nor the battle to the strong, neither yet bread to the wise, nor yet

riches to men of understanding, nor yet favour to men of skill.” Because

politics happeneth to them all. Or to the poor and the unconnected,

anyway.

No comments:

Post a Comment