by Shimshon Bichler and Jonathan Nitzan / November 22nd, 2013

Economic, financial and social commentators from all directions

and of all persuasions are obsessed with the prospect of recovery. The

world remains mired in a deep, prolonged crisis, and the key question

seems to be how to get out of it.

There is, however, a prior question that few if any bother to ask:

Do capitalists want a recovery in the first place? Can they afford it?

On the face of it, the question sounds silly: of course capitalists

want a recovery; how else can they prosper? According to the textbooks,

both mainstream and heterodox, capital accumulation and economic growth

are two sides of the same process. Accumulation generates growth and

growth fuels accumulation, so it seems bootless to ask whether

capitalists want growth. Growth is their lifeline, and the more of it,

the better it is.

Or is it?

Accumulation of What?

The answer depends on what we mean by capital accumulation. The

common view of this process is deeply utilitarian. Capitalists, we are

told, seek to maximize their so-called ‘real wealth’: they try to

accumulate as many machines, structures, inventories and intellectual

property rights as they can. And the reason, supposedly, is

straightforward. Capitalists are hedonic creatures. Like every other

‘economic agent’, their ultimate goal is to maximize their utility from

consumption. This hedonic quest is best served by economic growth: more

output enables more consumption; the faster the expansion of the

economy, the more rapid the accumulation of ‘real’ capital; and the

larger the capital stock, the greater the utility from its eventual

consumption. Utility-seeking capitalists should therefore love booms and

hate crises.

But that is not how real capitalists operate.

The ultimate goal of modern capitalists – and perhaps of all

capitalists since the very beginning of their system – is not utility,

but power. They are driven not to maximize hedonic pleasure, but to

‘beat the average’. This aim is not a subjective preference. It is a

rigid rule, dictated and enforced by the conflictual nature of the

capitalist mode of power. Capitalism pits capitalists against other

groups in society, as well as against each other. And in this

multifaceted struggle for power, the yardstick is always relative.

Capitalists are compelled and conditioned to accumulate

differentially, to augment not their absolute utility but their earnings

relative to others. They seek not to perform but to out-perform, and outperformance means

re-distribution.

Capitalists who beat the average redistribute income and assets in

their favour; this redistribution raises their share of the total; and a

larger share of the total means greater power stacked against others.

Shifting the research focus from utility to power has far-reaching

consequences. Most importantly, it means that capitalist performance

should be gauged not in absolute terms of ‘real’ consumption and

production, but in financial-pecuniary terms of relative income and

asset shares. And as we move from the materialist realm of hedonic

pleasure to the differential process of conflict and power, the notion

that capitalists love growth and yearn for recovery is no longer self

evident.

The accumulation of capital as power can be analyzed at many

different levels. The most aggregate of these levels is the overall

distribution of income between capitalists and other groups in society.

In order to increase their power, approximated by their income share,

capitalists have to strategically sabotage the rest of society. And one

of their key weapons in this struggle is unemployment.

The effect of unemployment on distribution is not obvious, at least

not at first sight. Rising unemployment, insofar as it lowers the

absolute (‘real’) level of activity, tends to hurt capitalists and

employees alike. But the impact on money prices and wages can be highly

differential, and this differential can move either way. If unemployment

causes the price/wage ratio to decline, capitalists will fall behind in

the redistributional struggle, and this retreat is sure to make them

impatient for recovery. But if the opposite turns out to be the case –

that is, if unemployment helps raise the price/wage ratio – capitalists

would have good reason to love crisis and indulge in stagnation.

So which of these two scenarios pans out in practice? Do stagnation

and crisis increase capitalist power? Does unemployment help capitalists

raise their distributive share? Or is it the other way around?

Unemployment and the Capitalist Income Share

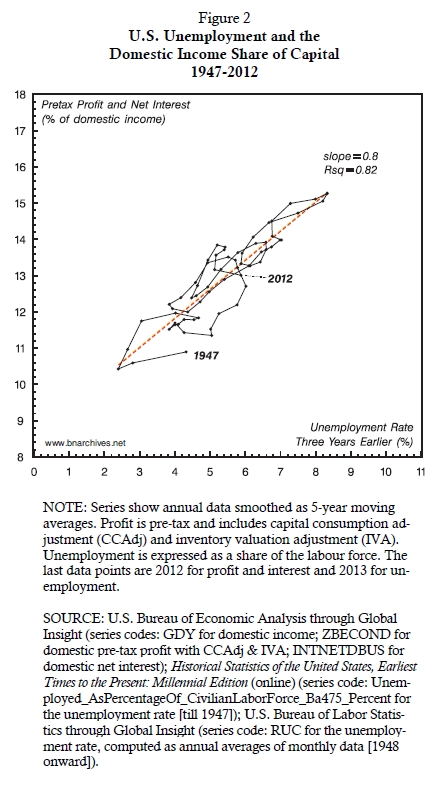

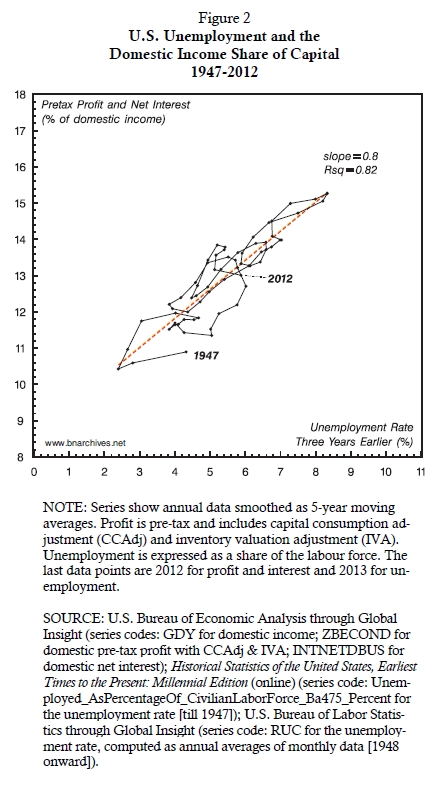

Figures 1 and 2 examine this process in the United States, showing

the relationship between the share of capital in domestic income and the

rate of unemployment since the 1930s. The top panel of Figure 1

displays the levels of the two variables, both smoothed as 5-year moving

averages. The solid line, plotted against the left log scale, depicts

pre-tax profit and net interest as a percent of domestic income. The

dotted line, plotted against the right log scale, exhibits the rate of

unemployment as a share of the labour force. Note that the unemployment

series is lagged three years, meaning that every observation shows the

situation prevailing three years earlier. The bottom panel displays

their respective annual rates of change of the two top variables,

beginning in 1940.

The same relationship is shown, somewhat differently, in Figure 2.

This chart displays the same variables, but instead of plotting them

against time, it plots them against each other. The capitalist share of

domestic income is shown on the vertical axis, while the rate of

unemployment three years earlier is shown on the horizontal axis (for a

different examination of this relationship, including its theoretical

and historical nonlinearities, see Nitzan and Bichler 2009: 236-239,

particularly Figures 12.1 and 12.2).

Now, readers conditioned by the prevailing dogma would expect the two

variables to be inversely correlated. The economic consensus is that

the capitalist income share in the advanced countries is

procyclical.

Expressed in simple words, this belief means that capitalists should

see their share of income rise in the boom when unemployment falls and

decline in the bust when unemployment rises.

But that is not what has happened in the United States. According to

Figures 1 and 2, during the post-war era, the U.S. capitalist income

share has moved countercyclically, rising in downturns and falling in

booms.

The relationship between the two series in the charts is clearly

positive and very tight. Regressing the capitalist share of domestic

income against the rate of unemployment three years earlier, we find

that for every 1 per cent increase in unemployment, there is 0.8 per

cent increase in the capitalist share of domestic income three years

later (see the straight OLS regression line going through the

observations in Figure 2). The R-squared of the regression indicates

that, between 1947 and 2012, changes in the unemployment rate accounted

for 82 per cent of the squared variations of capitalist income three

years later.

The remarkable thing about this positive correlation is that it holds

not only over the short-term business cycle, but also in the long term.

During the booming 1940s, when unemployment was very low, capitalists

appropriated a relatively small share of domestic income. But as the

boom fizzled, growth decelerated and stagnation started to creep in, the

share of capital began to trend upward. The peak power of capital,

measured by its overall income share, was recorded in the early 1990s,

when unemployment was at post-war highs. The neoliberal globalization

that followed brought lower unemployment and a smaller capital share,

but not for long. In the late 2000s, the trend reversed again, with

unemployment soaring and the distributive share of capital rising in

tandem.

Box 1

Underconsumption

The empirical patterns shown in Figures 1 and 2 seem consistent with

theories of underconsumption, particularly those associated with the

Monopoly Capital School. According to these theories, the oligopolistic

structure of modern capitalism is marked by a growing ‘degree of

monopoly’. The increasing degree of monopoly, they argue, mirrors the

redistribution of income from labour to capital. Upward redistribution,

they continue, breeds underconsumption. And underconsumption, they

claim, leads to stagnation and crisis. The observed positive correlation

between the U.S. capitalist share of income and the country’s

unemployment rate, they would conclude, is only to be expected.

There is, however, a foundational difference between the

underconsumptionist view and the claims made in this research note. In

our opinion, the end goal of capitalists is the augmentation of power.

This goal is pursued through strategic sabotage and is achieved when

capitalists manage to redistribute income and assets in their favour.

The underconsumptionists, by contrast, share with mainstream economists

the belief that capitalists are driven to maximize their ‘real’ capital

stock. From this latter perspective, favourable redistribution is, in

fact, detrimental to capitalist interests: the higher the

capitalist income share, the stronger the tendency toward

underconsumption and stagnation; and the more severe the stagnation, the

greater the likelihood of capitalists suffering a ‘real’ accumulation

crisis.

Employment Growth and the Top 1%

The power of capitalists can also be examined from the viewpoint of

the infamous ‘Top 1%’. This group comprises the country’s highest income

earners. It includes a variety of formal occupations, from managers and

executives, to lawyers and doctors, to entertainers, sports stars and

media operators, among others,

but most of its income is derived directly or indirectly from capital.

The Top 1% features mostly in ‘social’ critiques of capitalism,

echoing the conventional belief that accumulation is an ‘economic’

process of production and that the distribution of income is merely a

derivative of that process.

This belief, though, puts the world on its head.

Distribution is not a

corollary of accumulation, but its very essence. And as it turns out,

in the United States, the distributional gains of the Top 1% have been

boosted not by growth, but by stagnation.

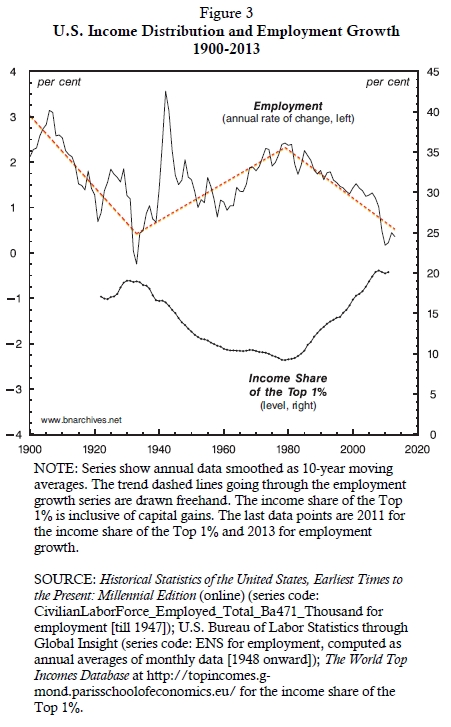

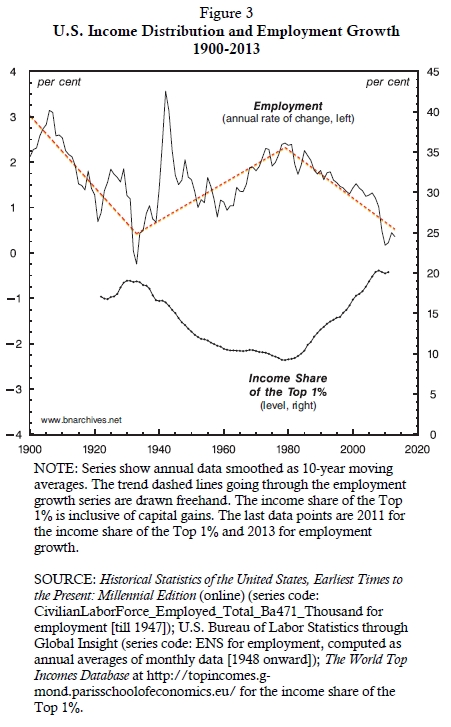

Figure 3 shows the century-long relationship between the income share

of the Top 1% of the U.S. population and the annual growth rate of U.S.

employment (with both series smoothed as 10-year moving averages).

The overall relationship is clearly negative. When stagnation sets in

and employment growth decelerates, the income share of the Top 1%

actually

rises – and vice versa during a long-term boom

(reversing the causal link, we get the generalized underonsumptionist

view, with rising overall inequality breeding stagnation – see Box 1).

Historically, this negative relationship shows three distinct

periods, indicated by the dashed, freely drawn line going through the

employment growth series. The first period, from the turn of the century

till the 1930s, is the so-called Gilded Age. Income inequality is

rising and employment growth is plummeting.

The second period, from the Great Depression till the early 1980s, is

marked by the Keynesian welfare-warfare state. Higher taxation and

spending make distribution more equal, while employment growth

accelerates. Note the massive acceleration of employment growth during

the Second World War and its subsequent deceleration bought by post-war

demobilization. Obviously these dramatic movements were unrelated to

income inequality, but they did not alter the series’ overall upward

trend.

The third period, from the early 1980s to the present, is marked by

neoliberalism. In this period, monetarism assumes the commanding

heights, inequality starts to soar and employment growth plummets. The

current rate of employment growth hovers around zero while the Top 1%

appropriates 20 per cent of all income – similar to the numbers recorded

during Great Depression.

How Capitalists Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Crisis

If we follow the conventional macroeconomic creed, whether mainstream

or heterodox, U.S. capitalism is in bad shape. For nearly half a

century, the country has watched economic growth and ‘real’ accumulation

decelerate in tandem – so much so that that both measures now are

pretty much at a standstill.

To make a bad situation worse, policy attempts to ‘get the economy

going’ seem to have run out of fiscal and monetary ammunition.

Finally, and perhaps most ominously, many policymakers now openly admit to be ‘flying blind when steering their economies.’

And yet U.S. capitalists seem blasé about the crisis. Instead of

being terrified by zero growth and a stationary capital stock, they are

obsessed with ‘excessive’ deficits, ‘unsustainable debt’ and the

‘inflationary consequences’ of the Fed’s so-called quantitative easing.

Few capitalists if any call on their government to lower unemployment

and create more jobs, let alone to rethink the entire model of economic

organization.

The evidence in this research note serves to explain this nonchalant attitude: Simply put,

U.S. capitalists are not worried about the crisis; they love it.

Redistribution, by definition, is a zero-sum game: the relative gains

of one group are the relative losses of others. However, in capitalism,

the end goals of those struggling to redistribute income and assets can

differ greatly. Workers, the self-employed and those who are out of

work seek to increase their share in order to augment their

well being. Capitalists, by contrast, fight for

power.

Contrary to other groups in society, capitalists are indifferent to

‘real’ magnitudes. Driven by power, they gauge their success not in

absolute units of utility, but in differential pecuniary terms, relative

to others. Moreover – and crucially – their differential

performance-read-power depends on the extent to which they can

strategically sabotage the very groups they seek to outperform.

In this way, rising unemployment – which hammers the well-being of

workers, unincorporated businesses and the unemployed – serves to boost

the overall income share of capitalists. And as employment growth

decelerates, the income share of the Top 1% – which includes the

capitalists as well as their protective power belt – soars. Under these

circumstances, what reason do capitalists have to ‘get the economy

going’? Why worry about rising unemployment and zero job growth when

these very processes serve to boost their income-share-read-power?

The process, of course, is not open-ended. There is a certain limit,

or asymptote, beyond which further increases in capitalist power are

bound to create a backlash that might destabilize the entire system.

Capitalists, though, are largely blind to this asymptote. Their power

drive conditions and compels them to sustain and increase their sabotage

in their quest for an ever-rising distributive share. Like other ruling

classes in history, they are likely to realize they have reached the

asymptote only when it is already too late.

*****

For our full paper on the subject, see: Shimshon Bichler and Jonathan

Nitzan, ‘Can Capitalist Afford Recovery? Economic Policy When Capital

is Power’,

Working Papers on Capital as Power, No. 2013/01, October 2013, 1‑36.

Research for this paper was partly supported by the SSHRC.

"The ultimate goal of modern capitalists – and perhaps of all capitalists since the very beginning of their system – is not utility, but power. They are driven not to maximize hedonic pleasure, but to ‘beat the average’. This aim is not a subjective preference. It is a rigid rule, dictated and enforced by the conflictual nature of the capitalist mode of power. Capitalism pits capitalists against other groups in society, as well as against each other."

ReplyDelete"The evidence in this research note serves to explain this nonchalant attitude: Simply put, U.S. capitalists are not worried about the crisis; they love it.

"Redistribution, by definition, is a zero-sum game: the relative gains of one group are the relative losses of others. However, in capitalism, the end goals of those struggling to redistribute income and assets can differ greatly. Workers, the self-employed and those who are out of work seek to increase their share in order to augment their well being. Capitalists, by contrast, fight for power.

"In this way, rising unemployment – which hammers the well-being of workers, unincorporated businesses and the unemployed – serves to boost the overall income share of capitalists. And as employment growth decelerates, the income share of the Top 1% – which includes the capitalists as well as their protective power belt – soars. Under these circumstances, what reason do capitalists have to ‘get the economy going’? Why worry about rising unemployment and zero job growth when these very processes serve to boost their income-share-read-power?"